Nepal’s Locally Elected Women Representatives

►Saraswati Katuwal

October 5, 2017

The successful completion of local, provincial, and federal elections in 2017 is an historic milestone for the country. Local elections were held after almost two decades. They became a key vessel for acting upon the Constitutional obligation towards gender and social inclusion in the government and ending the political impasse that beset the country for many years. Record number of women representatives were elected to office, and this has presented the representatives with both opportunities and challenges. The number of women especially from marginalized communities coming into power currently augurs well for gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) but, the road to women’s substantive participation in leadership and decision-making roles is littered with manifold challenges. Against this backdrop, The Asia Foundation in partnership with Samjhauta Nepal conducted a mix-method exploratory study in 20 rural/urban municipalities across the seven provinces to assess the existing needs and capacities of the locally elected women representatives along with the social, political, and economic challenges and opportunities that these women are faced with.

The data shows that majority of the women have basic level education with high percentage having undergone secondary level education and small percentage having gone for higher education. Only 12% of the surveyed women representatives were illiterate, and another 22% were just literate i.e. could do very basic reading and writing. This belies the general perception/belief that the current group of elected women representatives are largely uneducated compared to their male counterparts. It would be useful to do a comparative study on the education level of elected male representatives, and compare against the existing data on education level of elected female representatives. It is interesting to note that irrespective of their educational status, 89% of the surveyed women elected representatives were involved in social groups, development projects, community activities, and various other engagements including party politics prior to winning the election. However, only 4% of these elected representatives had any prior direct political experience. This is understandable because Nepal has not had local elections for 20 years, and provincial/federal elections do not provide as many opportunities and seats as local elections. Notably, 88% of women representatives were engaged in various economic activities like agriculture, business, social work/politics, and labor. Only 12% of these elected women representatives identified themselves as a housewife, and most identified themselves as being engaged in agriculture by professions, even if it constituted working on own farmland and they were not being paid or got direct remuneration. The fact that they made an economic and social distinction between the role of a housewife versus their involvement in any other economic activity

without direct financial remunerations, indicates a level of empowerment of these women, regardless of their educational status. Forty-seven percent of the elected women representatives were encouraged by political parties to stand in the election, and 22% were encouraged by community members. It is important to bear in mind that no political party would pick a candidate to run for elected office if they did not have the potential to win. Therefore, it indicates that the political parties had faith in these candidates to win, and that their selection as candidates was not “random.” However, data collected could not provide information on what each political party was looking for in terms of eligibility and qualifications from its candidates. Many women stated in the focus group discussions (FGDs) that it could be their rapport with the community or their previous engagements outside the home. Some of the women indicated in the FGDs that the political parties nominated them to fulfill the quota obligations. However, they were concerned that their lack of prior political experience could hamper their performance and current roles as elected representatives.

When asked if they faced any challenges at work, 53% women representatives indicated that they did, and 48% of these representatives reported having no idea how to tackle those challenges. The FGDs showed similar findings. Regardless of educational status or age, majority of the surveyed women representatives indicated that financial and budget management issues were challenging and trainings in these would help them perform better at work. They also indicated the need for leadership and empowerment training, training and information on law, the constitution, and government policies. The current elected women representatives are keen to use their first term to acquire that political experience and gain valuable lessons and insights into political governance. The findings and analysis of the study may be largely indicative given that the study sample is limited but more so because the present situation on the ground is dynamic. Yet, it cannot be denied that there is palpable excitement and optimism amongst elected women representatives to be an active participant in Nepal’s evolving governance structures. Tempering the optimism with realistic assessment of the challenges and work on hand is needed. Building capacities and supportive environment for women's leadership in local governance in the context of federalism in Nepal is needed. But more broadly, creating an enabling, gender-equal ecosystem for women's effective and meaningful participation in governance and in any activity, is crucial.

Share this with your friends:

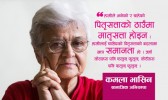

प्रत्येक महिला पुरुषभन्दा कमजोर छैनन् : कमला भासिन

नरेश ज्ञवाली ►

भदौ २७, काठमाडौं। दक्षिण एसियामा लैङ्गिक समानता, शिक्षा, गरिबी निवारण, मानवअधिकार र शान्तिका...

नरेश ज्ञवाली ►

भदौ २७, काठमाडौं। दक्षिण एसियामा लैङ्गिक समानता, शिक्षा, गरिबी निवारण, मानवअधिकार र शान्तिका...

पुरुष कलमले पूर्ण नारीलाई लेख्न सक्दैन

काठमाडौं। मान्छेहरू कडा भएर बोलेको भन्दा नरम भएर बोलेको मनपर्छ । खरा कुराभन्दा नरम, सरस र सलिल कुराहरू मनपर्छ । तर...

काठमाडौं। मान्छेहरू कडा भएर बोलेको भन्दा नरम भएर बोलेको मनपर्छ । खरा कुराभन्दा नरम, सरस र सलिल कुराहरू मनपर्छ । तर...

कालो तिलले कम्मर दुखेको र अनुहारमा भएको पोतोको उपचार गर्छ

काठमाडौं । कालो तिल अथवा तिलबाट प्राप्त हुने बिऊ तेल उत्पादनको लागि प्रयोग गरिन्छ । अनुहारमा चायाँ, पोतो वा दाग,...

काठमाडौं । कालो तिल अथवा तिलबाट प्राप्त हुने बिऊ तेल उत्पादनको लागि प्रयोग गरिन्छ । अनुहारमा चायाँ, पोतो वा दाग,...

दुबईमा पहिलो पटक नेपाली कल्चरल पहिरनको फेसन शो सम्पन्न

काठमाडौं। गत माघ २८ गते दुबईमा नेपाली कल्चरल पहिरनको फेसन शो पहिलो पटक फेसन फ्युजन २०१७ सम्पन्न भयो । एनआरएन...

काठमाडौं। गत माघ २८ गते दुबईमा नेपाली कल्चरल पहिरनको फेसन शो पहिलो पटक फेसन फ्युजन २०१७ सम्पन्न भयो । एनआरएन...

उमेर अनुसारको हुनुपर्छ खान्की, अनि मात्र मानिस स्वस्थ रहन्छ

काठमाडौं। पोषणको आवश्यकता उमेरअनुसार परिवर्तन हुन्छ । उमेरको हरेक अवस्थामा स्वयंलाई स्वस्थ राख्न शरीरलाई...

काठमाडौं। पोषणको आवश्यकता उमेरअनुसार परिवर्तन हुन्छ । उमेरको हरेक अवस्थामा स्वयंलाई स्वस्थ राख्न शरीरलाई...

यी भोजन खाए छाला सुन्दर हुन्छ !

काठमाडौं। स्ट्रबेरी : यो भिटामिन सीले भरपुर हुन्छ । भिटामन सीले छालालाई चाउरीबाट जोगाएर सधैं जवान राख्न मद्दत...

काठमाडौं। स्ट्रबेरी : यो भिटामिन सीले भरपुर हुन्छ । भिटामन सीले छालालाई चाउरीबाट जोगाएर सधैं जवान राख्न मद्दत...

मुलुकका सम्मानित पदमा महिलाको उपस्थिति, सबैका लागि आशाको ढोका उघारे

काठमाडौं। अहिले नेपालका तीनवटै अंगका प्रमुख महिला भएकाले नेपाली राजनीतिक क्षेत्रमा मात्र नभएर सामाजिक...

काठमाडौं। अहिले नेपालका तीनवटै अंगका प्रमुख महिला भएकाले नेपाली राजनीतिक क्षेत्रमा मात्र नभएर सामाजिक...

लोग्नेमान्छेको जात केटी देखेपछि.....

काठमाडौं । शान्ताको विवाह भएको पाँच वर्ष बितिसक्दा पनि छोराछोरी भएनन् बरु उनलाई एकाएक ब्लड क्यान्सर भयो । समयले...

काठमाडौं । शान्ताको विवाह भएको पाँच वर्ष बितिसक्दा पनि छोराछोरी भएनन् बरु उनलाई एकाएक ब्लड क्यान्सर भयो । समयले...

मनोसामाजिक समस्या के हो?

साउन ११, काठमाडौं । मनोसामाजिक समस्या भन्नाले मन र समाज वीच हुने समस्या हो । यो जो कोही व्यक्तिलाई पनि हुन सक्छ ।...

साउन ११, काठमाडौं । मनोसामाजिक समस्या भन्नाले मन र समाज वीच हुने समस्या हो । यो जो कोही व्यक्तिलाई पनि हुन सक्छ ।...

महिलाको दोस्रो विवाहको कुरा सुन्दा पढेलेखेकैले अनुहार बिगार्छन्

काठमाडौं। दोस्रो विवाहबारे मैले नसोचेको, नचाहेको होइन । तर, म मेरा आत्मीयसँग फेरि विवाह गर्नेबारे कुरा गर्छु,...

काठमाडौं। दोस्रो विवाहबारे मैले नसोचेको, नचाहेको होइन । तर, म मेरा आत्मीयसँग फेरि विवाह गर्नेबारे कुरा गर्छु,...